The Arda Library

Welcome, Tolkien Fan Traveler!

What a wonderful website for Tolkien fans. When the site's domain expired we lost so much information compliled in just one location. The new owners of the domain want to keep as much of the 2003 -2008 archived content in case Tolkien fans found their way back to the Royal Library of Menegroth. Alas, most of the original images were not recoverable.

Kudos to Daereth, the original owner of the Arda Library, for all your dedication.

And to all visitors....Enjoy this edited version of Daereth's site.

Welcome, Traveler!

By chance or by intent, you are now in the Royal Library of Menegroth, compiled and managed by Lady Melian (Daereth). I hope that you will enjoy your time here and find the Library to be a valuable guide to the world of Middle-earth, as so many have before you.

J Price writes Fan Mail: I am forever indebted to this website for getting my mind engaged in a very fun endeavor that is rewarding for its own sake, but also protecting me from myself. Before I discovered this resource, I was becoming engaged in a very destructive habit - I am an addictive gambler. I have been known to play US slots for 8 hours straight. Once I found casinos on the web, I moved my addiction to slots online and burned through thousands of dollars and hours. My daughter & I used to be into Tolkien long ago and when she turned me onto this site, my interest in gambling disappeared and I started spending all my time reading various posts about our favorite fantasies. I'm never going back and there's enough reading material online to keep my interest forever! But always start here.

Fantasy

Fantasy is now considered to be one of the most ancient literary genres. Many great epics and myths of old, such as The Tale of Gilgamesh and Beowulf can be referred to as the first fantasy books ever written.

In the course of ancient history, the basic elements of fantasy were taken over by a number of civilizations, and were thus incorporated into folk tales and legends. Unlike the majority of traditions of antiquity, fantasy was adopted and subsequently perfected by priests and storytellers of the Middle Ages.

Until the mid-20th century, fantasy was thought to be an authentic feature of epic literature of the past, never to be revived in the present-day industrial world. However, JRR Tolkien’s groundbreaking works, including The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion and The Hobbit, have rediscovered the traditions of fantasy and revealed its full capacities, revolutionizing out notion of modern literature.

Since 1953, the year when The Lord of the Rings was published, there has been an outbreak of fantasy-related works which flooded the bookstores all over the world. Some of them were based on Tolkien’s characters and settings, others introduced an absolutely new perspective on contemporary fantasy-writing.

In general, fantasy stories can be broadly split up into two groups: those which feature events taking place in an imaginary world, like Arda of Tolkien and the Discworld of Terry Pratchett; and those that are set in the world we are all familiar with, like the Tale of the Nibelungs. Writers who choose either point of view will face certain challenges. In the first case, conceiving a world would require a great deal of creativity on behalf of the author. One also needs to depict it in great detail, so that the reader’s every question about its structure can be easily answered. The characters’ actions should conform with the specific laws of that particular world, otherwise the tale won’t be convincing and it will become far too “fantastic” for most readers to appreciate.

On the other hand, if the story is set on Earth, one should always be in search of ways of incorporating magic and “fantasy” into the plot without actually distorting the reality as we perceive it. This technique has been used with great skill in JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

What is it that makes fantasy so special? First of all, it is based on magic. The first legitimate purpose of fantasy is to introduce a touch of unreal action into life. That is why most stories involve plots based on wizardry, sorcery, witchcraft and other magic phenomena. Imaginary worlds are often inhabited by magical creatures: trolls, elves, goblins, dwarfs, ogres, golems, leprechauns, fairies and, last but not least, dragons.

To summarize the plots of thousands and thousands of fantasy books, it is enough to say that the one thing always present is the conflict between Good and Evil. Deep psychological analysis, reflecting on what is evil and what is not, is not quite common. In most cases, there is a straightforward Good and a straightforward Evil, opposite in theor strivings and beginnings. Other important elements of fantasy plpots are loyalty and betrayal, lover and hate, envy, greed and valor.

Following this brief overview are the synopses of the three greatest fantasy books ever written.

The Lord of the Rings

Gandalf, one of the Istari, discovers that a golden ring that Bilbo Baggins owns is actually the One Ring, forged by the Dark Lord Sauron in the Cracks of Doom, possessing a power great enough to destroy the world. Frodo Baggins, the courageous and mischievous hobbit, is faced with the immense task of taking the Ring back to Mordor across the realms of Middleearth. There he must cast it back into the Fire, and thus foil the Dark Lord in his evil purpose.

The Hobbit

Is an account of events which took place sixty years before the Ring was discovered. Whisked away from his smug hobbit-hole by Gandalf the wizard, Bilbo Baggins finds himself involved in a plot to raid the hoard of Smaug the Dragon, and to help the folk of Thorin recover their ancient stronghold.

The Silmarillion

Is a story of the heroic Fist Age of Middleearth. It is also the story of the rebellion of Feanor and his kinsfolk against the gods, their exile from Valinor, and the realms of ancient Beleriand, ruled by valiant men and wise Elven-kings. The Silmarilli were three perfect jewels fashioned by Feanor the Fiery, the most gifted of the Elves. When Morgoth, the First Dark Lord, stole the jewels for his own ends, the Elves waged a long and terrible war to recover them. The Silmarillion, a genuine creation myth, tells of the estrangement of the races of Men and Elves, the Siege of Angband, and the fiver great battles of the First Age, hopeless despite their heroism.

The Silmarillion was published along with several shorter stories: Ainulindale, Valaquenta, Akallabeth and Of the Rings of Power, which tell of the events preceding the Creation of Arda, the downfall of Numenor and the War of the Ring.

THE SILMARILLION

The Silmarillion…

The Silmarillion, which is the epic legendary precursor to The Lord of the Rings,is to Tolkien’s Arda what the Bible is to Earth. It is an ancient drama to which the characters in The Lord of the Rings look back, and in whose events some of them, such as Elrond and Galadriel, took part. The tales of The Silmarillion are set in an age when Morgoth, the First Dark Lord, dwelt in Middleearth, and the High Elves made war upon him for the recovery of the Silmarils.

Indeed, the most simplified description of Quenta Silmarillion, or The Silmarillion proper, would be to describe it as a cosmogenic (creation) myth. Although JRRT is unanimously considered the author of all the legends and tales of which it is composed, The Silmarillion was rendered suitable for publication, edited and supplied with comments and appendices by Christopher Tolkien, the writer’s son.

After the death of JRRT, Christopher was faced by the formidable task of analyzing the decrepit notebooks and tattered sketches containing the subject matter of what would later become known as The Silmarillion.

Despite having been published two decades after The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion is the backbone of Tolkien’s creative heritage. The first legends can be traced way back to the early 1920s, when even The Hobbit was far from completion. As years went by, the initial design underwent gradual changes. Many new details were incorporated into the story, other parts were narrated over and over again, supplying the text with features intrinsic to a magnificent creation myth, which it surely is.

As a result, in the early 70s The Silmarillion existed rather as a compilation of random texts and sketches than a single-volume work. Christopher Tolkien managed to put the bits together like a jigsaw puzzle, to reconcile the controversial moments and make the individual stories coherent in style, which is no mean feat.

The name The Silmarillion is derived from the Elvish name for three jewels, the Silmarils, around which the story revolves. Even though this is the main line of plot, two other works – Ainulindale (the Song of the Ainur) and Valaquenta (the Account of the Valar) are essential for its full understanding.

The Ainulindale is an account of the creation of Arda and the earliest days of the world. According to Tolkien, first there was Eru Iluvatar, the supreme god, who with his thoughts gave life to the Ainur, his servants and helpers. The greatest of the Ainur, known as Valar, the Powers of Arda, and lesser spirits called Maiar sang in front of the throne of Iluvatar to the melody that he revealed to them. But every time the Ainur raised their voices in unison, one of them, Melkor, wanted to interweave elements he alone had imagined that were not in accord with Iluvatar’s design, into the chanting. Thus he started a discord, and many voices fell silent, while others joined in with his tune. And so controversy was ingrained into the essence of Arda, for later Melkor and his followers turned aside from the way of Light, and soon they fell from pride to envy, from envy to anger and into the abyss of darkness and hatred for all things beautiful.

Despite their interference, the three motives of the Song were completed, and then by the word of Iluvatar the Ainur beheld the world they had wrought with their singing.

The Valaquenta is the tale of the Ainur who descended into Arda and shaped the newborn world. Among them were eight Aratar, the Lords of the Valar, who never returned to the halls of Iluvatar and chose to forever stay in Arda.

They were assisted in their work by Valar of lesser powers, and a legion of Maiar, some of who later sided with Melkor and worked for the world’s undoing. They were known as Balrogs, Valaraukar, the Demons of Might. The most dreaded of Melkor’s servants was Sauron. The former student of Aule, he ever craved for more power and knowledge, and when the Valar denied him the authority he wanted, he turned to Melkor and became his faithful ally. Even after Melkor was overthrown, Sauron remained the servant of evil and was rightfully called the Second Dark Lord. In the Third and Second Ages, Sauron took up his abode in Mordor and there gathered his army of orcs, wanting to lay the whole of Arda at his feet.

The Silmarillion is a logical sequel of the two previous parts. Although even the basic turns of the plot are nearly impossible to recount, much less to cover in a synopsis, it can be safely stated that the conflict revolves around the Silmarils, three beautiful jewels fashioned by Feanor, the most gifted of the Elves. They were creations of unrivaled beauty, for in them was imprisoned the unsullied light of the Trees of Valinor. Melkor tried to lure Feanor to his side, but he revealed the enemy’s evil designs and denied him his trust, naming him Morgoth, the Black Enemy. In revenge, Morgoth stole the Silmarils and brought them to be guarded in the fortress of Angband in the north of Beleriand.

The Noldor swore undying vengeance on anyone who would lay their hands on the Silmarils, and devoted their lives to their recovery. But such was the Curse of the Noldor that they had laid upon themselves that they never got their precious gemstones back. The rest of the saga is like an unending quest for the Silmarils, in the course of which Elven kingdom are established and destroyed, wars are waged and heroic feats are performed. The pivotal stories are the Lay of Leithian – of the love of Beren and Luthien – and the tale of Turin Turambar. The Silmarillion ends when Morgoth is overthrown and banished out of the fringes of the world.

Akallabeth recounts the downfall of the great island kingdom of Numenor and the Second Age. Sauron, who had survived the fall of Morgoth, seduced the Numenorean king into worshipping the Dark Lord. The king gathers a huge fleet to wage a war upon the Valar, but is of course downcast. In this very moment, Numenor is devastated, the only survivors being those loyal to the Valar.

Of the Rings of Power is a huge time leap away from the previous stories, and tells of the Realms in Exile, that is, kingdoms found in Middleearth by the survivors of Numenor’s ruin. During these times, Sauron returns to Middleearth, and tricks the Elves by having them forge the Rings of Power. For himself he makes the One Ring, and with its help endeavors to make Arda his sole dominion. The last tale of The Silmarillion tells of how Men and Elves formed an alliance against Sauron and were victorious in the war; and of the One Ring, which was lost…

for a time anyway.

Tidbits of Information

Farmer Giles of Ham did not look like a hero. He was fat and red-bearded and enjoyed a slow, comfortable life. Then one day a rather deaf and short-sighted giant blundered on to his land. More by luck than skill, Farmer Giles managed to scare him away. The people of the village cheered: Farmer Giles was a hero. His reputation spread far and wide across the kingdom. So it was natural that when the dragon Chrysophylax visited the area it was Farmer Giles who was expected to do battle with it!

"Farmer Giles of Ham" bears the distinction of being the only one of Tolkien's fairy tales to have been placed in a known region and an approximate time frame.

"Of the history of the Little Kingdom few fragments have survived: but by chance an account of its origin has been preserved: a legend, perhaps, rather than an account; for it is evidently a late compilation, full of marvels, derived not from sober annals, but from the popular lays to which its author frequently refers. For him the events that he records lay alreday in a distant past; but he seems, nonetheless, to have lived himself in the lands of the Little Kingdom...." 1

With this curious explanation, J.R.R. Tolkien suggests that we are about to read a work which arises from the same traditions as the tales of Arthur and Robin Hood. "Giles" is a bit of forgotten English folklore celebrating that half-imagined, mostly-forgotten time after the Saxons came and before they drove the Celts into the mundane woods and hills. The Latin names and references make it clear that Giles is a Briton, a late generation remnant of the old empire after the decline of the western authority of the Romans.

Tolkien throws in a mysterious reference to a larger compendium, now lost to us, when he concludes his Introduction to "Giles" with:

"...There are indications in a fragmentary legend of Georgius son of Giles and his page Suovetaurilius (Suet) that at one time an outpost against the Middle Kingdom was maintained at Farthingho. But that situation does not concern this story, which is now presented without alteration or further comment, though the original grandiose title has been suitably reduced to Farmer Giles of Ham."2

Giles was a farmer living in Ham who gained a small measure of fame when he accidentally shot a giant in the nose with his blunderbuss. The presence of the blunderbuss in the story is a quaint anacronism, of course, and to be construed as an embellishment by some later author. Giles was rewarded by the King of the Middle Kingdom, Augustus Bonifacius, with a sword named Caudimordax. The sword was more well known as "Tailbiter", and it was a powerful weapon against dragons.

The giant, who had blundered into Ham only because he'd gotten lost on one of his walks through the countryside, eventually spread a few tall tales among his friends and relatives to cover up his embarrassment. And he didn't realize he had been shot with a blunderbuss, but instead thought he had been stung by horseflies. Word reached the ears of the dragon Chrysophylax that there were no more dragon-slaying knights in the lands to the east of his mountains, so he went off to enjoy the fruits of the giant's imagination.

Which brought him up against Giles, now armed with Tailbiter. Giles like everyone else in Ham expected the King to dispatch a few knights to take care of the dragon, but the knights were afraid the dragon would dispatch them, so they found excuses not to take up the quest. And so Giles was left to cope with the dragon in what became a battle of wits -- a battle for which Giles was not well armed.

In the end Giles accepted a promise of ransom from the dragon and he let Chrysophylax go. This of course led to King Augustus' hearing about treasure and wanting his fair share (or his Kingly share, which would be more than fair). So Giles eventually had to help hunt down Chrysophylax after the dragon failed to return with his promised ransom, and once again Tailbiter gave him an edge. But Giles was finally beginning to see the light of day and instead of being greedy or overly loyal to the King, he made an alliance with the dragon and took only part of the treasure home with him.

The story makes light of the great dragon-slaying traditions. The knights who are supposed to do the job cannot, and they are useless fops more intent on discussing "precedence and etiquette" than on noticing dragonsign (huge footprints littering the landscape). "Giles" is also an interesting commentary on how people react to danger. Heroes aren't simply called for, they are demanded and hapless farmers who stand in the way of giants are bound to be made into heroes.

The sloth and greed of kings is counterbalanced by the courage and everyday practicality of the common, who give rise to kings and kingdoms. "Giles" provides us with an example of how anyone can become king if he sees an opportunity and takes advantage of it. Of course, it helps to have a magic sword and a reasonably dutiful flame-breathing dragon by your side

The Tolkien Encyclopedia

Later events concerning the membersof the Fellowship of the Ring(the Shire Reckoning)

|

The Family Trees

Represented here are some of the family trees of the royal houses of Middle-earth, as well as the lineage of some of the most important characters in The Lord of the Rings and the Silmarillion. These easy-to-use charts should help you get to grips with the family relationships among some of the royal families, which many readers find confusing. The first three tables come from the Appendices of the LOTR.

|

Bilbo's Birthday Party

The famous celebration of the 111 the birthday of the venerable hobbit Bilbo Baggins took place on September 12th, year 3001 of the Third Age. A great many guests were invited, among them most of the Tooks and Bagginses – the distant relatives of Master Bilbo. The celebration was that significant because it was Frodo’s birthday as well, and a special one – he was turning 33, which is with hobbits the time of the coming of age. Just as Bilbo promised Gandalf the Wizard in the movie version of the book, this was a night to remember. The Shire-folk were reveling on the glade around the party tree, enjoying Gandalf’s famous fireworks, premium ale from Bilbo’s own cellars and dancing – that us, until the farewell speech. All of a sudden, Bilbo bid a farewell to his relatives and disappeared into thin air by putting on his magic ring, which was later discovered to be the One Ring of Sauron. In the following confusion, Bilbo packed up and set out for Rivendell in a company of dwarves. He left the Ring, although not without hesitation, and not without Gandalf’s help, into the keeping of Frodo.

The Shortened Biography

{tohl'-keen}

The English writer and scholar John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, b. Bloemfontein, South Africa, Jan. 3, 1892, d. Sept. 2, 1973, reestablished fantasy as a serious form in modern English literature. As professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University, he presented (1936) the influential lecture "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," an aesthetic justification of the presence of the mythological creatures--Grendel and the dragon--in the medieval poem; he then went on to publish his own fantasy, The Hobbit(1937). There followed his critical theory of fantasy, "On Fairy-Stories" (1939), and his masterpieces, the mythological romances The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) and The Silmarillion (1977).

Brought to England as a child upon the death of his father in 1896, Tolkien was educated at King Edward's School in Birmingham and at Oxford. He enlisted in 1915 in the Lancashire Fusiliers; before leaving for France, he married his longtime sweetheart, Edith Bratt. Tolkien saw action in the Battle of the Somme, but trench fever kept him frequently hospitalized during 1917. He held academic posts in philology and in English language and literature from 1920 until his retirement in 1959.

Tolkien began writing The Hobbit in 1936. For a number of years previously he had been inventing languages for the mythical place—Middle Earth—that is the setting for the The Hobbit and had been writing stories about Middle Earth as well (which were published posthumously as The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales [1980]). The Hobbitwas soon quite popular, and Tolkien was asked for a sequel by his publisher. In 1937 he began work on what would eventually be published as The Lord of the Rings. The work consists of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King.This remarkable work by the mid-1960s had become, especially in its appeal to young people, a sociocultural phenomenon. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set in a mythical past; the latter work chronicles the struggle between various good and evil kingdoms for possession of a magical ring that can shift the balance of power in the world. The trilogy is remarkable for both its subtly delineated fantasy types (elves, dwarves, and hobbits) and its sustained imaginative storytelling. It is noteworthy as a rare, successful modern version of the heroic epic. An animated film version of the first two books of the trilogy appeared in 1978.

Inclination and profession moved Tolkien to study the heroic literature of northern Europe--Beowulf, the Edda, the Kalevala. The spirit of these poems and their languages underlies his humorous and whimsical writings, such as Farmer Giles of Ham (1949) and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1962), as well as his more substantial works.

Bibliography

The Monster and the Critics and other Essays

The Hobbit

Leaf by Niggle

Farmer Giles of Ham

Lord of the Rings

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

On Fairy Stories

Tree and Leaf

Smith of Wootton Major

The Road Goes Ever On (with Donald Swann)

Finn and Hengest

Mr Bliss

Pictures by JRR Tolkien

Sir Gawain, Pearl and Sir Orfeo

The Father Christmas Letters

The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth

Edited by Christopher Tolkien

The Silmarillion

Return of the Shadow

Unfinished Tales Morgoth's Ring

Sauron Defeated

The Book of Lost Tales Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales Part 2

The Lays of Beleriand

The Lost Road and other Writings

The Shaping of Middle-earth

The Treason of Isengard

The War of the Ring

The Archives of Middle-earth on

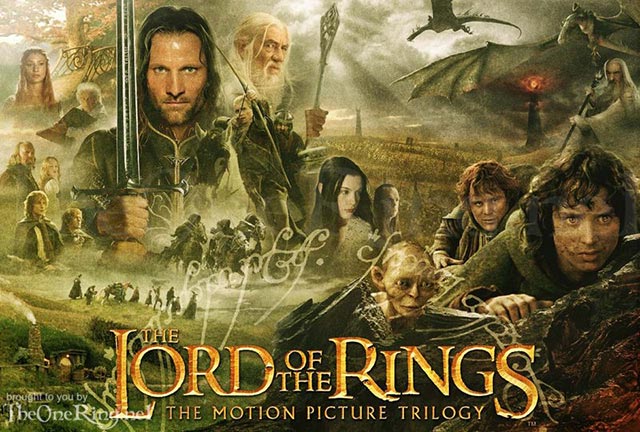

The Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit movies

The LOTR II…

Opening with the recollection of Gandalf’s fall in Moria, Peter Jackson’s spectacular sequel to the Oscar-winning Fellowship of the Ring carries on with the story of the hobbits’ quest into Mordor, seemingly hopeless despite their heroism… Aragorn and his companions are faced with a new peril: the treason of Isengard and Saruman’s planned assault on Rohan, the free land of the Horselords… A skillful combination of large-scale battle and siege scenes with romance and true Elvish magic, the film is an outstanding masterpiece of the modern fantasy genre. Complemented with the superb acting of the ever-charismatic hobbit Elijah Wood and the beautiful Elf-princess Liv Tyler, the film is a magnificent yet at times intensely frightening experience.

|

<>Later events concerning the members of the Fellowship of the Ring (the Shire Reckoning) u>

|

Melian's Crafts of the Archives of Middle-earth

/images/Melian.jpg

Welcome! Melian's Crafts of the Archives of Middle-earth is an exclusive section meant solely for the development and sharing of ideas on the crafts of Middle-earth. You will do well to remember that this is the domain of Queen Melian and, of course, her cat called Mish, who will give you advice on how to use the section best.

Here, we feature several crafts. The most important one perhaps is cross-stitching. When practiced with much love and patience, it can be upgraded to tapestry-making. Some knitting and crochet has also found its way into the Crafts workshop.

The unique nature of this section is the way that it features patterns and ideas related to the world of Middle-earth. Therefore, what you see here will not be found anywhere else on the web. If it is, it is copied from this website.

Assidi (Gluck Skywalker) and Ingvall Koldun

Black Lord FAQ

[ Q ] Does the Black Lord write white poems?

[ A ] Of course not. In versification he mows under Sasha Cherny.

[ Q ] Does the Black Lord sleep in a white night?

[ A ] No. He saves this dream for a rainy day.

[ Q ] Does the Black Lord suffer from delirium tremens?

[ A ] No , if you drink "Black Russian"

[ Q ] Will the Black Lord join the Green Party?

[ A ] He will not look at his feet - he will definitely enter.

[ Q ] Will the Black Lord be taken to the Red Army?

[ A ] Yes, because the White Guard already has a Black Baron.

[ Q ] Do maidens love the Black Lord?

[ A ] Unfortunately, only dirty girls ...

[ Q ] Does the Black Lord’s army have light heads?

[ A ] Yes, but only on the bayonets of his glorious attack aircraft.

[ Q ] Do Red Khmers serve the Black Lord?

[ A ] No, he cannot pronounce their name without coughing.

[ Q ] Does the Black Lord read the yellow press?

[ A ] If it is not too blackened there.

[ Q ] Can the Black Lord get into the yellow house?

[ A ] Now, I will ask a psychiatrist. Hey, Morgot Takhkhisovich? Can the Black Lord get into the yellow house?

[ Q ] Is the Black Lord listed in the Red Book?

[ A ] Yes, but its area is a white spot on the map.

[ Q ] Will the White Sea be Black if we bathe the Black Lord in it?

[ A ] Yes, if the Black Lord himself repaired and greased his Thai fighter.

[ Q ] Can I invite the Black Lord to the white dance?

[ A ] Only if you are a White Lady.

Gluck Skywalker, Ingvall von Prikoll

The Tolkien FAQ

got any Tolkien-related questions?

What was the relationship between Orcs and Goblins? (entry from the Tolkien Monster Encyclopedia)

They are different names for the same race of creatures. Of the two, "Orc" is the correct one. This has been a matter of widespread debate and misunderstanding, mostly resulting from the usage in the The Hobbit (Tolkien had changed his mind about it by The Lord of the Rings but the confusion in the earlier book was made worse by inconsistent backwards modifications). There are a couple of statements in the The Hobbit which, if taken literally, suggest that Orcs are a subset of goblins. If we are to believe the indications from all other areas of Tolkien's writing, this is not correct. These are: some fairly clear statements in letters, the evolution of his standard terminology, and the actual usage in The Lord of the Rings, all of which suggest that "Orc" was the true name of the race. (The pedigrees in Tolkien: The Illustrated Encyclopedia are thoroughly inaccurate and undependable.)

What happened was this.

The creatures so referred to were invented along with the rest of Tolkien's subcreation during the writing of the Book of Lost Tales (pre-The Silmarillion). His usage in the early writing is somewhat varied but the movement is away from "goblin" and towards "orc". It was part of a general trend away from the terminology of traditional folklore (he felt that the familiar words would call up the wrong associations in the readers' minds, since his creations were quite different in specific ways). For the same general reasons he began calling the Deep Elves "Noldor" rather than "Gnomes", and avoided "Faerie" altogether. (On the other hand, he was stuck with "Wizards", an "imperfect" translation of Istari ('the Wise'), "Elves", and "Dwarves"; he did say once that he would have preferred "dwarrow", which, so he said, was more historically and linguistically correct, if he'd thought of it in time...)

In the The Hobbit, which originally was unconnected with the The Silmarillion, he used the familiar term "goblin" for the benefit of modern readers. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, however, he'd decided that "goblin" wouldn't do - Orcs were not storybook goblins. Thus, in The Lord of the Rings, the proper name of the race is "Orcs" (capital "O"), and that name is found in the index along with Ents, Men, etc., while "goblin" is not in the index at all. There are a handful of examples of "goblin" being used (always with a small "g") but it seems in these cases to be a kind of slang for Orcs. Tolkien's explanation inside the story was that the "true" name of the creatures was Orc (an anglicised version of Sindarin Orch , pl. Yrch). As the "translator" of the ancient manuscripts, he "substituted" "Goblin" for "Orch" when he translated Bilbo's diary, but for The Red Book he reverted to a form of the ancient word.

Where did Tolkien get the names for his characters from

It is indeed hard to trace back the origins of all the names of Tolkien's characters. E.g. the word ORC is derived from the name of a Roman god of named Orcus. The name EARENDIL was borrowed by Tolkien from the Crist of Cynewulf

Eálá Earendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended

- "Hail Earendel brightest of angels, over Middle Earth sent to men ".

I came across EOMER in Beowulf, and my best advice to those thinking that nothing will surprise you about Tolkien is to flip through the first couple of pages of the Elder Edda to meet Balin, Dwalin, Fili, Kili, Thorin, Thror and many others.

Where can I find reliable info on Tolkien languages?

A very good question. You can either check out the old Languages section of the website or try the Encyclopedia of Arda or Ardalambion for extra info

Why was this site created?

For the sole purpose of collecting ALL possible information on the creatures of Tolkien, as well as his world. I do realize though that this job is actually too big a piece of work for anyone to handle on his/her own. So if any of you out there would like to cooperate, I would appreciate any kind of help.

Who is the webmaster of the site?

The webmaster, designer and owner, is me, Daereth. I won't be wasting time telling you about my aliases and personalities in the world of Tolkien... One of the important things to know is that my first Arda personality is a half-orkish one (actually it is quarter-orkish), the other one is Lady Melian, the Maia who lived in Doriath, and yet another is related to Rohan. When I am asked for what an image of my fantasy character would be, I usually give a few. Here is my current favorite.

Who is the author of the articles published?

I have been busy compiling the articles for the Tolkien Encyclopedia for more than two years. I am the author of all the encyclopedia articles, unless stated otherwise. Some single articles in the Characters of the Dark section of the encyclopedia are the only exceptions. A few of the smaller ones were taken from the Silmarillion index.

Can I borrow your articles?

I believe you may. The only thing you have to do if you finally got that bit of info you've been browsing for for ages, is to link to us. A link to www.daereth.net will suffice, and an authorship notice (Daereth) will also be appreciated.

Please note that the images in the Fan Art gallery are exempt from this rule. You may download images from this site, but if you want to place them on your web, be sure you have the artist's permission as well.